Higher education institutions are increasingly relying on predictive analytics to increase student success. Data collection and analysis allow institutions to identify areas where students may benefit from additional support.

You can use student data to track academic progress, recommend helpful solutions when grades fall, and help individuals determine their ideal career paths. Understanding how higher educational analytics are shifting and how to use them successfully can help you increase your institution’s graduation rates.

There’s been a big shift on campus, according to panelists and attendees at the Inside Higher Ed conference Untapped Data: Enhancing Teaching and Learning. Higher education is moving away from using campus data solely for compliance reporting and toward using data to manage the institution, support student outcomes, and enhance teaching and learning. Here are five key takeaways from the day’s conversations:

“Organizational culture is fundamentally critical,” said Jack Suess, vice president of IT and CIO of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “Data technology is necessary, but never sufficient. There has to be a partnership across the university: Institutional Research, enrollment management, the provost’s office, IT. It takes a group working together to do this well.” If there’s too much effort on technology, you’ll under-resource other areas; if you underinvest in technology, you can’t get the data you need, Suess noted.

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast,” Webster Thompson, executive vice president of business development at Watermark, reminded the audience, referring to management guru Peter Drucker’s famous statement. “In our experience working with thousands of institutions, [success or failure in using data] is never about the technology.”

Good data can challenge long-standing assumptions. Travis Reindl, senior communications officer at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, shared an example from Georgia State University’s remarkable, data-driven success story. “One ‘aha’ moment was discovering that registration errors were very consequential. They set off a chain of events that led to attrition,” Reindl said. These errors might include taking a class out of sequence or before prerequisites were met. “Getting into the wrong class led to drop/add, withdraw/fail. It was a navigation issue, not a capability issue,” Reindl said.

“If you look at any university, there are a large number of departmental or campus academic policies, such as GPA or gateway courses, which were created before we had data to know if they really are predictors,” Suess said. “Data gives you a chance to go back and look at policies to see if they’re right.”

Noted data skeptic Jerry Z. Muller, professor at The Catholic University of America and author of The Tyranny of Metrics, shared his concerns about the potential pitfalls of data, including cost and the perceived pressure to lower standards to meet an institution’s graduation-rate metric.

Moderator Scott Jaschik, founder and editor of Inside Higher Ed, countered with an example from a University of North Carolina campus that used data to uncover what factors were keeping many students from graduating in four years. “They discovered that, in most cases, students were within two courses of completion, so they decided to waive tuition for the summer before senior year, and four-year graduation rates went way up,” Jashik said. “It was a big win using data, with no change of standards.”

The data needed to understand and improve student outcomes, change policies and practices, and better manage the institution are often housed in different systems or offices. In addition, the data is sometimes incompatible, so can’t readily be combined for analysis. These data silos inhibit the use of data campus-wide to answer both big-picture and single-issue questions.

Panelists and audience members advocated for aligning data systems to break down silos so administrators and faculty have better access to the full range of campus information. In addition, “we need to make data consumable, and really easy to use,” said Rachelle Hernandez, the University of Texas’s senior vice provost for enrollment management.

“Good data doesn’t answer questions,” Debra Humphreys, vice president for strategic engagement at Lumina Foundation told Jaschik. “Data, well designed, helps you ask additional questions.”

“Data is a tool, not a solution. [It’s easy to make] the mistake of not thinking hard enough about how we’re using the data,” said Tiffany Jones, director of higher education policy at The Education Trust. There is, Jones noted, an over-reliance on available data. “We are sometimes making use of existing data that’s far beyond what it can really be useful for,” Jones said. “Data can be powerful, but we have to consider the quality of available data versus the ideal data we should be collecting” to inform decisions.

Throughout the event, panelists and attendees spoke of the need to overcome data silos created by gathering data in different places for different uses, without the ability to share it across the institution. They also stressed the importance of a shift away from a compliance-based focus and toward a proactive focus on better serving students and steering the institution. Finally, they advocated for using data to raise the questions that allow substantive improvement and innovation on campus, all in service of students.

Data can help your higher education institution identify areas for improvement and determine where you need to support students more effectively. Approximately 32.9 percent of undergraduate students leave college before finishing their degree, but a new approach to using data can help you increase graduation rates. To use data effectively, your institution’s faculty and administration should strive to accomplish the following:

Data patterns and trends can help you recognize when students may need additional support. Noticing academic needs early in a student’s educational progress allows you to provide the proper resources for that student’s success. If they fall behind in certain courses, academic advisors and student success coaches can recommend tutoring services or provide tips for improvement.

You can use data to track each student’s grades and indicate when their performance may be below what they need for a certain career path. This information can help them pivot to alternative opportunities if necessary. For example, if an undergraduate student’s grades fall below a nursing program’s admission requirements, the student can consider a different but equally rewarding career path, such as physical therapy or medical sonography.

The goal is not to discourage students but to help them plan the most successful career path for their skills, abilities, and interests. Helping students redirect their career plans can significantly increase graduation rates. While a student may start higher education with a specific career in mind, graduating from a program they excel in is better than staying in a program they find significantly challenging and eventually drop out of.

Using data to track student progress should encourage and motivate students. Avoid using data to discourage individuals and instead use it to help them plan for success. If a student falls behind, help them get excited about how much a tutor could help them improve and succeed. If their grades indicate a different major and career path would be ideal, inspire them to explore new interests and passions.

Successful data analysis and application also depend on ethical practices. Your institution must prevent biases and stereotypes from reinforcing inequality, so it’s important to ensure data focuses on performance and behavior instead of student backgrounds and ethnicities.

Some institutions default to focusing only on students with significantly dropping grades below a C-plus. However, reaching out to the in-between students with grades between a C-plus and a B-minus can help them catch up with their academic progress faster and easier than they would otherwise. Extending additional support to students when their grades begin to fall is much more effective than waiting until they fall significantly.

Predictive analytics are incredibly useful for tracking student progress and performance. Using campus data effectively can help you increase retention and graduation rates while supporting each student’s academic and professional journey.

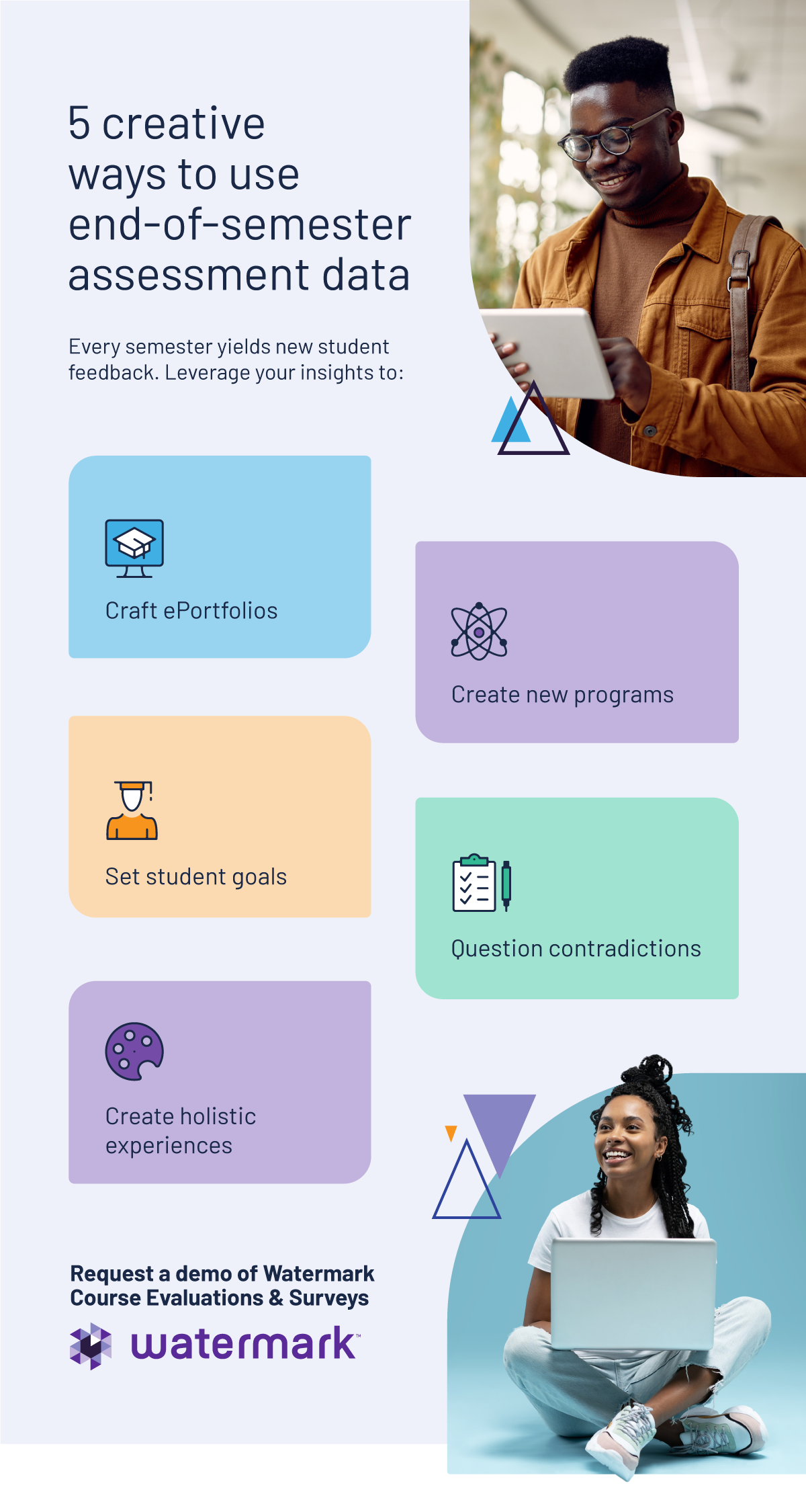

Watermark offers data collection, measurement, and analysis software you can use to enhance student engagement and outcomes. Watermark Student Success & Engagement software uses artificial intelligence (AI) to intuitively gather data, predict potential outcomes, and provide recommendations and solutions. Contact us to request a demo and learn more about how you can increase student success.