Many community college students balance their pursuit of academic success with a job, family, or both, and around a third are first-generation students blazing their own trail in higher education. These factors make community college students ideal candidates for one-on-one success coaching with a focus on soft-skill development, goal setting, academic improvement, and orientation to campus resources.

Community colleges implementing success coaching have seen their students reap benefits in perseverance, academic performance, and credential attainment. This guide explains how success coaching positively impacts students and how to achieve optimal results from success coaching at your community college.

Why community college students need success coaching

Community college students who stand to gain the most from success coaching are those grappling with one or more of these challenges:

- Being a first-generation student: Without the guidance of previous graduates in their family, first-generation students can lean on success coaches to help them navigate their higher education journey.

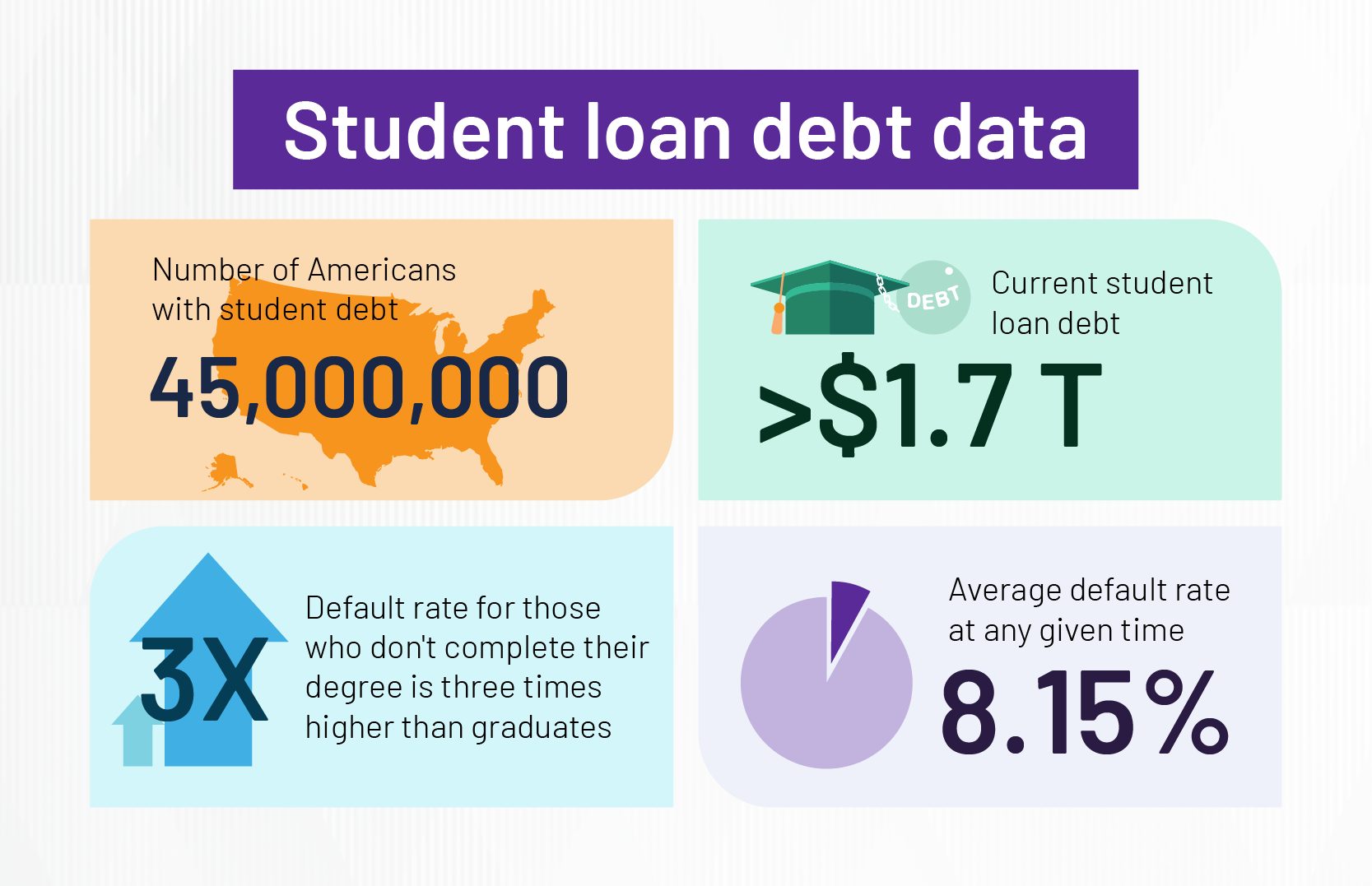

- Financial concerns: Affordability concerns are one of the top reasons community college students drop out, and students aiming to pay their way by balancing work and classes often struggle. Success coaches can point these students to financial aid and scholarship opportunities and mentor working students who want to improve their time management skills.

- Limited soft skills: Along with time management, academic success at community college relies on work ethic, goal setting, communication, and collaboration. Many students entering community college have had limited support in developing these soft skills, and success coaches can help address any weaknesses.

- Lack of connection: A sense of belonging is key to student success and engagement. However, some students, especially nontraditional ones, lack strong ties to campus communities. Success coaches can help them plug into student clubs and organizations while mentoring them in social skills development.

The top 10 positive impacts of success coaching for community college students

If your community college aims to start or expand a success coaching program, expect to see significant results over time. Here are the top 10 positive impacts of success coaching for students.

1. Personalized advice

Success coaching gives students a tailored advising experience, accounting for their unique backgrounds, needs, and goals. This advice can go beyond course selection and credit requirements to cover study skills, career prospects, and holistic well-being. Student data analytics and consistent student-coach relationships support maximal personalization in success coaching.

2. Guided goal setting

Coaches and students can collaborate on personalized SMART goals. While inspiring students to cast their own vision of academic success, coaches can help them clarify timelines, milestones, and methods. This process models goal-setting skills for students while motivating them to take ownership of their progress.

3. Improved engagement and satisfaction

The coaching relationship is a safe point of contact from which students can feel supported to connect with faculty and peers, enhancing their confidence and well-being. This, combined with personalized guidance and goal setting, makes the college experience more engaging and satisfying.

4. Enhanced skills development

Coaching sessions can equip students with skills that are vital to academic and career success but are seldom an explicit focus of course curricula. These skills include:

- Emotional intelligence

- Time management

- Study methods

- Critical thinking

- Problem-solving

- Communication

- Collaboration

- Leadership

5. Timely resource sharing

Success coaches can identify the study and support resources a student would most benefit from and proactively share them. These resources include:

- Financial aid

- Tutoring services

- Mental health counseling

- Career services

- Accessibility support

By referring students to these resources, coaches can help overcome the reluctance and uncertainty some students feel toward seeking help.

6. Elevated academic performance

Coaches can identify key academic improvement opportunities and provide study habit coaching, mentorship, and tutoring recommendations tailored to each student’s needs and learning styles. This can translate into higher GPAs and greater academic confidence.

7. Strengthened resilience

With the constant support of their coach, students can learn effective strategies to manage stress, overcome challenges, and adapt to change. Acquiring and applying these tools in the real-world arena of community college forges resilient individuals ready for success in the classroom and beyond.

8. Increased persistence

The support, encouragement, and mentorship that success coaches provide can help students overcome academic obstacles and persist to graduation. One study showed a 6 percent increase in fall-to-fall retention and an 8 percent increase in fall-to-next-spring retention when community colleges implemented success coaching.

9. Higher credential completion

Success coaching can improve a student’s likelihood of completing their qualification. However, the extent of this positive impact depends on success coaching implementation factors like:

- Faculty buy-in.

- Coaching experience consistency.

- Integration between coaching and the learning management system.

- The quality and quantity of communication around the success coaching program.

Research shows that success coaching with institutional buy-in can lead to a 9 percent increase in credential completion and a 12 percent increase when a student remains with the same coach throughout their studies.

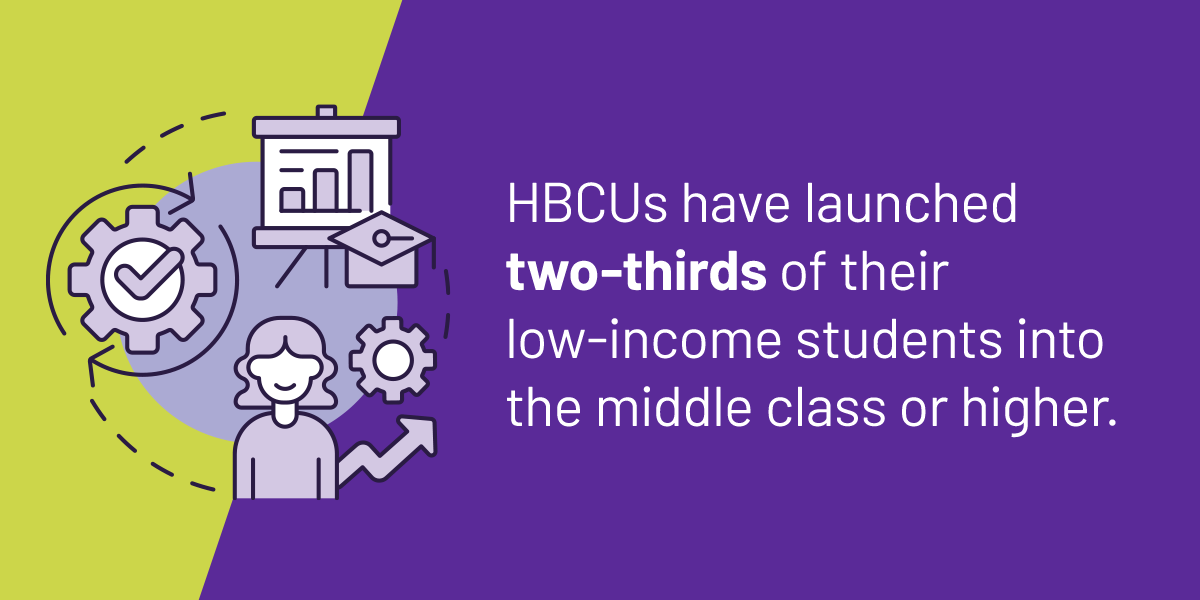

10. Greater equity

A success coaching program can help minority, first-generation, and at-risk students excel in the classroom and persist to graduation. For example, studies have shown retention improvements ranging from 8 percent to 50 percent among Black students with success coaches. This support makes a vital contribution toward closing equity gaps between the academic outcomes of student demographics.

How to optimize success coaching for community college students

Here are four ways to maximize your success coaching results:

- Prioritize faculty buy-in: Campus-wide buy-in, especially from faculty members, is essential to increase awareness and motivate student participation in the program.

- Harness data: Leverage data to improve coaching through student surveys, as well as predictive analytics to flag at-risk students for proactive interventions.

- Personalize coaching: Help coaches personalize the student experience by maintaining coach-student pairings until graduation when feasible. Student performance and engagement data can also help inform personalization.

- Integrate with technology: Use learning management and student support platforms to communicate about the program, streamline session scheduling, and track progress.

Enhance your community college success coaching with Watermark

Effective success coaching implementation at your community college can improve performance, retention, and equity among your students. As an industry-leading provider of higher education software, Watermark partnered with the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS) to study the positive impacts of combining our solutions with success coaching. This study of 11 schools, called the Minority Male Success Initiative (MMSI), showed a 22.4 percent retention boost when institutions implemented Watermark Student Success & Engagement and hired student success coaches.

Student Success & Engagement can help your community college:

- Guide students through personalized coaching pathways.

- Harness predictive analytics to prompt early coaching interventions for at-risk students.

- Equip your students with a native mobile app to schedule coaching appointments from anywhere.

Request a free demo of Student Success & Engagement today to see how we can enhance success coaching at your community college.