As an experienced Coordinator for Success Coaches at Tiffin University in Ohio, Susan Marion shares with Watermark how her work with students has helped her identify the different types of intelligent students who struggle in college.

Over the span of my career, I’ve worked with gifted students of all ages and found that intelligence alone is no guarantee of success. And while colleges’ struggles with retention often have more to do with students who enter the university setting academically underprepared for the content and rigor of college-level material, I have seen plenty of very bright, capable students on the verge of failing out of school.

Some of them face financial, family, or medical issues that hamper their ability to stay enrolled. But most of these bright students find themselves facing blocks of a more psychological nature. My experiences and insights have allowed me to identify three common manifestations of “smart student syndrome.”

The understimulated student is a very straightforward case: They are bright students who are not challenged enough in their current curriculum. They might find their classes too easy or repetitive of what they have already learned in other classes at your institution or even high school.

Brilliant students might already be familiar with the concepts and information, but understimulation can make it hard for them to get motivated about their classwork and homework, leading to increased absenteeism, missed assignments, or slipping grades. Students might even face long-term consequences; if the class is a prerequisite, they might be held back from proceeding with their studies.

Solutions for this student type can take many forms, depending on the student’s unique circumstances and background. Some potential solutions academic coaches can suggest to this student type include:

Academic coaching is essential for these students to develop a plan specific to their needs. It also provides somewhere students can vent their concerns and have someone listen to them.

I had one student in particular, a freshman named Eli, who suffered from this strain of smart student syndrome. Eli came from a very small, rural school district with few advanced-level classes and little special programming for bright students. Because of this, Eli felt, not surprisingly, unchallenged in school.

However, this was the only reality Eli knew, so his 13 years of experience had convinced him that that’s just how school was: not challenging and thus boring. Eli brought this same mentality into the college setting, and his grades started to suffer almost immediately.

During one of our meetings, I asked Eli about a particular class he was taking in international security studies. He told me that he was bored and that he thought the professor was dumbing down the material for the class. I asked, “Well, what interests you about this subject? What would you like to learn?” His eyes brightened and he immediately started talking animatedly about his interests.

“Okay then,” I offered. “Why don’t you go to your professor and bring up this very topic with him? If there’s anything professors love most, it’s when a student actually shows interest in the subject in which they have spent their careers becoming knowledgeable, and maybe you will become more invested in the class as a result!”

Eli gave me the deer-in-headlights look I almost always get from students when I suggest instigating a one-on-one conversation with a professor, but he agreed to give it a shot. When Eli walked into my office later that week, he was gushing. “Did you know that Professor Carradine came here straight from a career at the Pentagon?!” Apparently, Eli and Professor Carradine had spoken for more than an hour, and from then on international security studies was his favorite class.

Another type of bright student who struggles when they reach higher education is those who believe that this stage of their education will be just like high school or other institutions they attended. The transition into higher education is challenging for students in many ways — for many, this is their first taste of independence and the first time they have full control over their educational, personal, and social lives.

Expectations about higher education based on personal experiences can leave students falling behind when they have to face reality. They might lack the skills they need to thrive in classes that prioritize academic materials and discussions or group work. Alternatively, they might need to shift their mindset or habits to reflect the patterns and skills they need to succeed in a new learning environment.

Academic advisors and professors can foster student success by encouraging students to rise to the challenge or connecting them with the right resources to thrive in a new academic setting. For example, academic success centers can help teach students how to properly study, take notes, participate in discussions, and more, so that all students can do well in their classes.

Alright, it’s time to make a confession. I am a former “hasn’t adapted to the New World Order,” sufferer of smart student syndrome. Just like the students whose experiences in K-12 education convince them that school is not challenging and therefore a waste of time, there are others who come to different yet equally wrong conclusions.

For me, it wasn’t that school was boring. In fact, I was that kid who loved school so much that she would remind teachers when they had forgotten to assign homework — a tendency for which I would like to now publicly apologize — but that school was easy and therefore often didn’t require all that much work.

Yes, there were teachers who pushed me, who challenged me to achieve my full potential, and I was incredibly self-motivated when it came to subjects I was passionate about. However, I never had to work as hard as some other students did to get good grades. Then I went to college and everything changed. After a brief but significant learning curve, I realized that in order to succeed in college I would have to work much harder than I ever had previously — but that realization didn’t happen overnight.

Now, as a success coach, I see the same delayed revelation in some of the students who end up in my office. When these students find themselves on academic probation or warning, most are shocked. “How can this be?” they ask incredulously.

It’s as if they’ve been driving a car on paved roads for years, and then one day they try to drive a car on a lake. When the car starts sinking, their initial reaction is to say, “Something’s wrong with this car!” when in reality, different environments require different vehicles.

Usually, with these students, my job is all about speeding up that learning curve by making them aware of the change that has occurred. “College is not high school,” I remind them. And since these students usually enjoy being pushed and challenged once they’ve wrapped their minds around what is expected of them, they come to thrive.

This might be the most virulent form of smart student syndrome and, unfortunately, there is no definitive cure. Some students are simply so terrified of the prospect of ever being wrong, of “failing” even a little bit, that they’d rather quit mid-journey or not try at all. They think, “If I can’t do this as easily or as well as I have been able to do things in the past, then I don’t want to do it!”

Sometimes, this need to always be perfect has been instilled by parents or a particular school environment and sometimes it is self-imposed, but regardless of the origin, it can inch very capable students toward the edge of an academic cliff.

I have seen students bomb multiple choice tests because of their inability to make a decision when not 100% sure they are correct. Or drop a class because they got a C on the midterm. Or fail a class because they were too afraid to admit to anyone that they needed help.

As with the New World Order students, awareness is important. I remind them that they are not supposed to know everything at the age of 18 or 20 (or 30 or 40 or…), and that even if they were the smartest kid at their high school, a lot of college students were the smartest kids at their respective high schools.

I tell them that college resets the bar, and the most important thing is not that you are perfect but that you are on the path to achieving your goals. Thomas Edison once famously said that he was only able to invent the light bulb because of the thousands of times he failed at inventing the light bulb, and if failure is good enough for Thomas Edison, well…

Recently, I read a book about the differences in traditional Western and Eastern pedagogies. It focused, in part, on the idea that, while Western cultures often put the idea of intelligence on a pedestal, Eastern cultures focus much more on the importance of perseverance and the value of struggle.

By the time they get to college, some of my students who’ve spent nearly two decades being told how smart they are find themselves underperforming, or even failing, because they have yet to hone these less “testable” but equally important life skills. Our job as success coaches, as always, is to help these students become not only better educated but also stronger, wiser, and better able to tackle whatever challenges college life may throw at them.

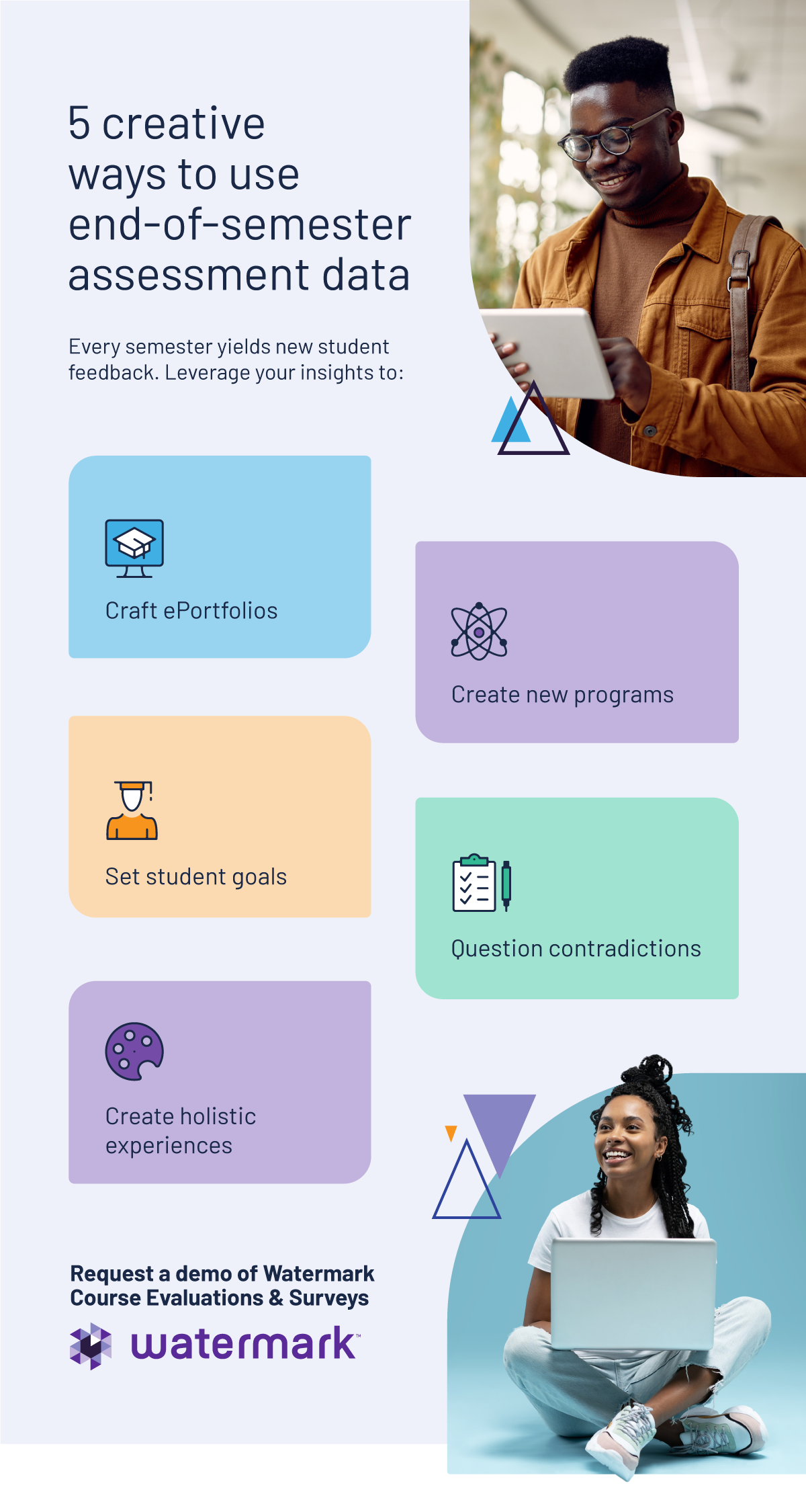

Some students feel they are too smart to fail or need help adjusting to a new way of learning. Academic advising and coaching can support every type of struggling student by connecting them with someone who can help. Watermark provides higher education institutions with powerful data collection and management solutions, enabling administrators and institutional decision-makers to better understand the student population.

Watermark Student Learning & Licensure helps faculty understand how each student progresses throughout their academic career. Faculty members can also give feedback to help students improve while they study and work with your institution. Watermark Student Success & Engagement tracks and measures student engagement, helping educators identify at-risk students and boost retention.

Request a demo today and discover how Watermark can support your students at your higher education institution.