Disruption seems like too benign a word to describe the experience of students and institutions this spring in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. Watermark recently held a panel conversation with Bliss Adkinson, Associate Director for Academic Affairs and SACSCOC Liaison, University of Northern Alabama; Tracey Floto, Executive Director of Assessment and Accreditation, Trine University; and Susan Brooks, Assistant Professor of Teaching in Education and Team Leader for the Intervention Specialist Program, University of Findlay about how they’re approaching assessment in light of changes caused by the pandemic.

Special thanks to Natasha Jankowski, Executive Director of the National Institute of Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA), for leading this great conversation about teaching and learning, reflection and action, and demonstrating the true spirit of continuous improvement.

Here are three ways the panelists identified to make assessment more relevant — and even more effective — in the wake of the recent crisis.

Panelists and attendees acknowledged the tremendous strain on faculty caused by the abrupt shift to emergency online teaching, including supporting students through this difficult time and balancing remote work in their own lives. Given these realities, how much can or should institutions expect from faculty in terms of capturing assessment data?

In her role at NILOA, Jankowski has been involved in many conversations as institutions grapple with managing assessment. “We are seeing a variety of changes to reporting forms to encompass a more reflective component or only a reflection focus in a report,” Jankowski said. “We’ve also seen outreach to better understand what type of learning data faculty need to feel prepared for the summer or fall term.” This ensures assessment serves as a faculty support rather than just a task to complete.

“Some faculty have indicated they are really overwhelmed,” panel attendee Candace shared. She noted that her institution is “using the HEDS surveys to see large-scale responses to what has been helpful for learning and to see how we are doing institutionally.” Additionally, they are allowing some grace with spring assessments, allowing faculty in some departments and certain accredited schools to determine which learning outcomes collection and assessment they do now. As a result, some are moving forward as usual while others are deferring some activities. Most of all, the institution is encouraging units to identify successful and unsuccessful strategies in the various remote environments, then documenting those discussions and determining how they will use that information.

“This is not just an issue of how do we do assessment, but it’s also ‘how do we learn, how do we work, and how do these things fit together’? There’s been a shift not just in modality — it was a life-wide change for our learners, for our faculty, and for ourselves,” Jankowski said. The role of assessment is “supportive, helping us make sense of and plan for [COVID impacts on teaching and learning].”

Before COVID struck, Trine University’s online division spent this academic year striving to improve its ADA compliance, which gave the rest of the institution a leg up in managing the challenges of remote learning when COVID struck. For example, “Trine Online was already thinking about students who are colorblind, and how that affects their ability to do online work,” Floto noted. Those insights have helped inform the university’s efforts to improve the online experience for students.

Jankowski acknowledged the real-time tension between compliance and improvement that is playing out in COVID-challenged institutions. While accreditation reporting requirements remain a constant, “There’s a very real understanding that assessment data is being used to think about future planning and being responsive to students’ needs,” Jankowski said. In the context of COVID, institutions are gaining a better understanding of equity issues, as well as what has and hasn’t worked for students in the shift to remote learning. All of this information will help them prepare for summer and fall.

“Our top priorities in assessment have been students’ technology needs and the capacity for learning in a remote environment,” noted Scott, an attendee. “This has allowed us to adapt and more forward with goal planning for future semesters.”

Patty, another attendee, agreed. “Internet access has been an issue,” for her institution’s students, she noted. “Some students had computers that were not compatible with our LMS with their internet access. Rural areas have a very different capacity than what is common for non-rural areas.”

Trine also modified its course evaluation surveys in order to capture qualitative data. “We decided that a numeric value of ‘how successful was the teacher in this course’ wasn’t going to give us the information that we needed,” Floto said. The institution opted to ask two open-ended questions: What did the professor do well in the course? And what could the professor do to improve the course? The survey garnered surprisingly useful results. “We’re hearing from faculty that they do feel like the responses have been more substantive,” Floto noted. Rather than “this class stinks” or “this professor is wonderful,” students have given specific examples of what worked and what didn’t.

Floto noted that students had the opportunity to share what was important or meaningful to them: “In some cases, students answered with things that happened at the beginning of the semester, so we didn’t lose that data by focusing on just the transition to online work.”

Through the surveys, Trine discovered that COVID-19 challenged their fully online students as well as those who started the semester in seated classes. “We have students who are parents who are working from home and finding that they’re now also teachers of their children during online learning for them,” rather than doing their own course work when their children were at school, Floto said. In addition, “They might not have had connectivity issues in the past, but have them now,” Floto said. “Maybe their plan for completing their online courses was to work during lunchtime at work,” rather than using their connectivity at home, so COVID disrupted their usual ability to complete coursework.

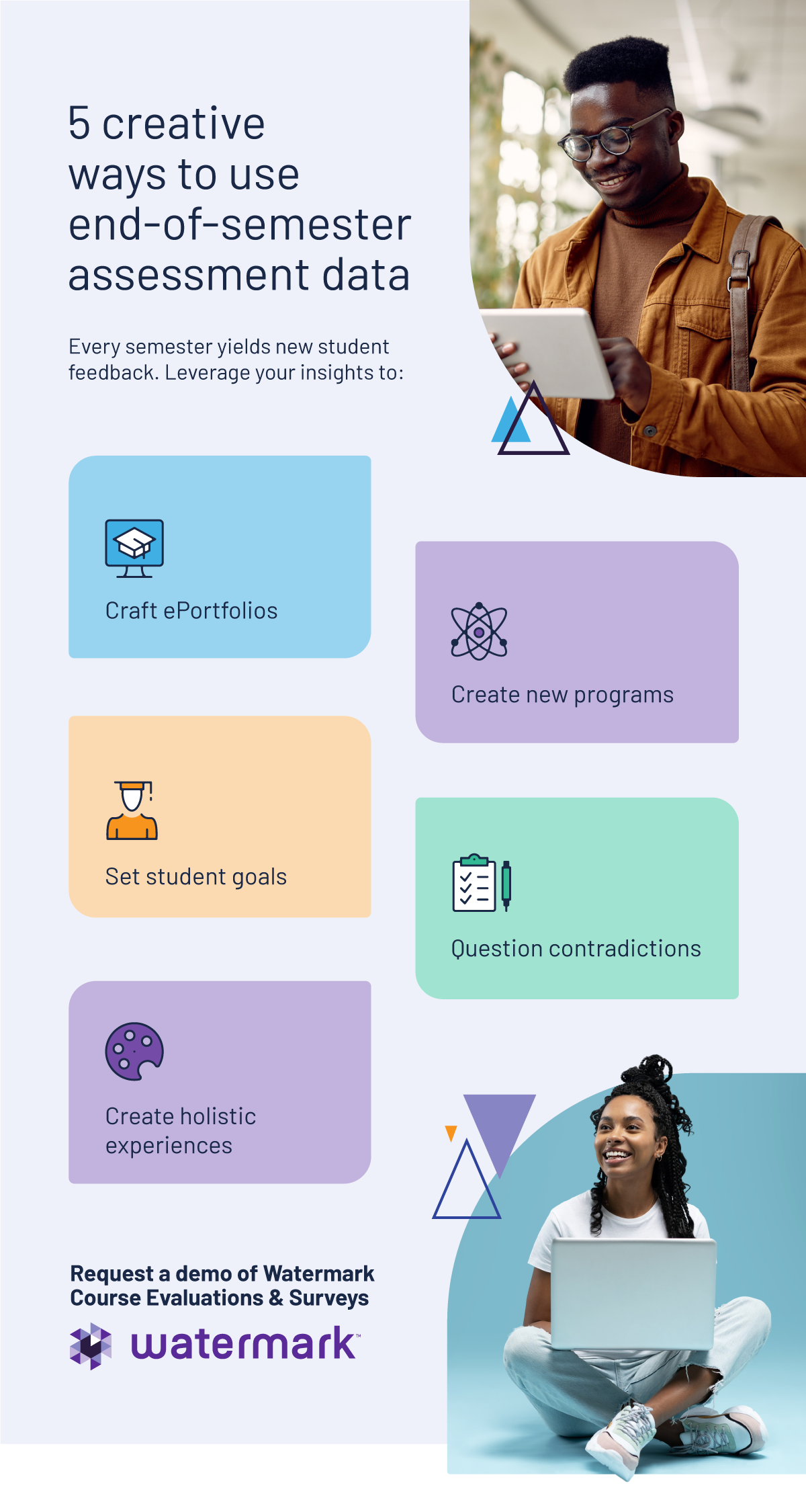

When participant Michelle asked, “Is anyone else using this as an opportunity to take a breath and rethink how assessment happens in your programs, particularly for programs that struggle with meaningful assessment?” panelists were quick to agree.

NILOA is seeing “an increase in opportunity for reflective assignments and assessments to have people really think about where they are in their learning process, what they’re learning,” Jankowski noted. “We’re also seeing a huge range of innovation and adaptability on the part of faculty in response to, ‘Well, I can’t just have everyone record a video for an oral communication. I need to think about something else.’ And in some ways it’s a really nice fundamental return to assessment basics. What do we want people to learn? What’s our main learning outcome and what does it look like in a variety of ways to demonstrate that?”

While the University of Northern Alabama is continuing its assessment strategies so it doesn’t have a gap in accreditation reporting, they have had many conversations about how to more effectively use assessment to improve student learning, beginning with what they called “rapid improvement events.”

“We got on a Zoom call for a couple of hours and really talked with the faculty of the department. We said, ‘Okay, let’s map this out and see if we can streamline some of your assessment processes.’ [Then we] improved processes to make sure we do what we need to be doing to give us information that we need to improve, but that we’re not doing a whole bunch of extra work,” Adkinson said. “It’s a great opportunity to really look at your processes, at how and why you’re assessing and be reflective about that.”

In addition, Northern Alabama decided to continue its usual practice of meeting with liaisons from each program near the end of the academic year to give them feedback on their assessment. “We found a way to do that, just work in a 30 to 60 minute conversation with them to really look at their processes. April is when we start that, and it gives us an opportunity to connect and communicate,” Adkinson said.

As a smaller institution, University of Findlay doesn’t have an office of institutional effectiveness. “It becomes a little more challenging, because everyone is sort of a worker bee,” Brooks said. “So we’re looking at how faculty and governance committees coordinate this information. Our role has been more collegial, [focused on] collaboration,” Brooks said. “We have worked to streamline and keep lines of communication open and transparent, helping each other without getting in each other’s way.”

At Trine, Floto’s team reached out to faculty to offer support, including sending faculty an “outcome survey” asking them to “Take a look at what your outcomes are. Can you still meet those with the transition you’ve had to make? How are you going to assess those outcomes?” Floto said. “We didn’t need a big explanation. We just needed them to really think through the process.” When the data came back, if there were issues that faculty identified or outcomes that couldn’t be addressed, they were able to work with deans and chairs to come up with a way so that students still had access to that learning.”

Though Trine recognized the need to continue its accreditation work, “One of the big priorities coming from [COVID disruption] is, What worked? What worked well and what didn’t work so well, and how we can use that information going forward?” Floto said. “We’re going to have a new normal, and we don’t know exactly what that’s going to look like. The ‘new normal’ could just be ever-evolving.”

To hear more from our panelists and participants about assessment in the wake of COVID, read about the decisions these institutions made to keep calm and collect on, or watch the on-demand recording.