“Uncertainty” is quickly becoming a buzzword, but in the time of COVID-19, it’s an accurate assessment of the state of higher education surveys and evaluations. Teaching and learning have been dramatically transformed as institutions have been thrust into virtual classrooms mid-semester, and remote instruction is a completely new experience for many faculty members and students.

Everyone is adjusting to new tools, technologies, and techniques, and the volume of change is making it difficult to measure our current reality. Faculty are concerned about how evaluation results will impact their review, promotion, and tenure, while administrators want to gather useful data that can help students and instructors make the most of their online learning experience.

We asked a panel from diverse institutions and backgrounds to discuss their course evaluation plan this term and beyond. Our conversation with Pam Jones, Coordinator – Surveys & Credit Arrangements at Swinburne University of Technology (AU); Robyn Marschke, Director of Institutional Research at University of Colorado – Colorado Springs (UCCS); and Christa Smith, Academic Effectiveness Analyst at Washburn University revealed some common threads in their approach to course evaluations in the time of COVID-19 that could help you define your own path forward.

All three of our panelists are opting to “stay the course” for spring evaluations, sticking to the same administration timelines, offering the same access to responses, and using the same survey instruments with, in some cases, slight variations. “We felt it was important for students to have an avenue to express how they felt the quality of instruction was this semester,” said Smith. “We just want to show that we’re keeping this consistent, that they can count on us to do this and that we value students’ opinions and their experiences with their courses.”

The panelists agreed that acknowledging the unique circumstances of this semester is important, while still maintaining consistency with past end of semester evaluations. Most questionnaires went largely unchanged, while panelists provided flexibility for programs to adjust their course survey length or add additional evaluation survey questions. At Washburn, one college opted to shorten their end of class survey questions from 50+ to just five, and all other units were given the option to add an open-ended, neutral question so students could provide additional comments.

“Our open ended question was along the lines of ‘If you would like to make an additional comment for this course, especially given the extraordinary circumstances of COVID-19 this semester, please do so in the response box below.’ So we’re giving them an avenue to respond, but it’s not required.” Smith said. These virtual classroom survey questions should help assess the new student experience.

At Swinburne, students are typically sent a four-question check-in survey early in the term, and faculty members use these insights to quickly address issues and make adjustments. (The Australian academic year begins in late February to early March.) “Swinburne feels now more than ever is the time to seek students’ feedback on this current learning environment and resources in the hope that we can continue to assist and support all aspects of their study and university life.” Jones said. “Our early check-in survey has just four questions, two of which are quantitative, on a 10-point Likert scale. Those questions are their satisfaction so far and their confidence at that stage in passing the course. Along with that we have two qualitative questions: best aspects and suggestions for improvement.”

Swinburne altered this term’s initial survey in response to COVID-19. “The questions in the adjusted survey were compiled to focus on gathering feedback on how students were finding the online experience so far and we wanted to know if there was any other support we could provide or improvements that we could make to the existing support that was being offered,” Jones said. “We added in a couple of quantitative questions to gauge the students’ satisfaction with the communication they were receiving from the faculty and the students’ ability to use the online resources through their internet and devices. Our qualitative question at the end was then reworded to ask if we could possibly provide any additional support to them during this period of disruption.”

As you think about your course surveys and evaluations, consider asking questions that can help your institution provide the right kind of support to students and faculty. UCCS considered asking students questions about the types of resources they need (for example, whether they have broadband or Wi-Fi, or what type of device they have). “We were leaning toward additional questions that would result in actionable items, so that the university could actually provide the resources,” Marschke said. “We just didn’t know what resources were needed.”

In addition, her team considered asking faculty questions to help determine the best approach for future terms, including what specific pedagogical changes were made, whether they delayed deadlines, if syllabi or course content was adjusted, and the impact of these changes on students.

Due to the rapid shift to online instruction, the courses faculty designed for the spring term look a lot different than they did pre-COVID. As instructors and students adjust their expectations, the panelists agreed that administrators will also need to adjust their plans for evaluations.

All of the panelists indicated they wouldn’t be using evaluations from this term to make promotion and tenure or rehiring decisions, but the feedback collected in the surveys will still be provided to faculty to help them adjust their approach in the current term and beyond. “I’d like to caution that we should not be assessing whether instructors were successful in transitioning to online instruction this semester. We are engaging in emergency remote teaching, for a lot of us, and online instruction looks very different. I’ve been told by some of my assessment colleagues that it takes about a hundred hours to develop a course for online,” said Smith. “We don’t want faculty to think that we can adequately and reasonably assess the work they’ve done to modify their course to online instruction with one survey. I think what we really want to do is use this to glean information from students on how to plan for the summer and potentially the fall being online.”

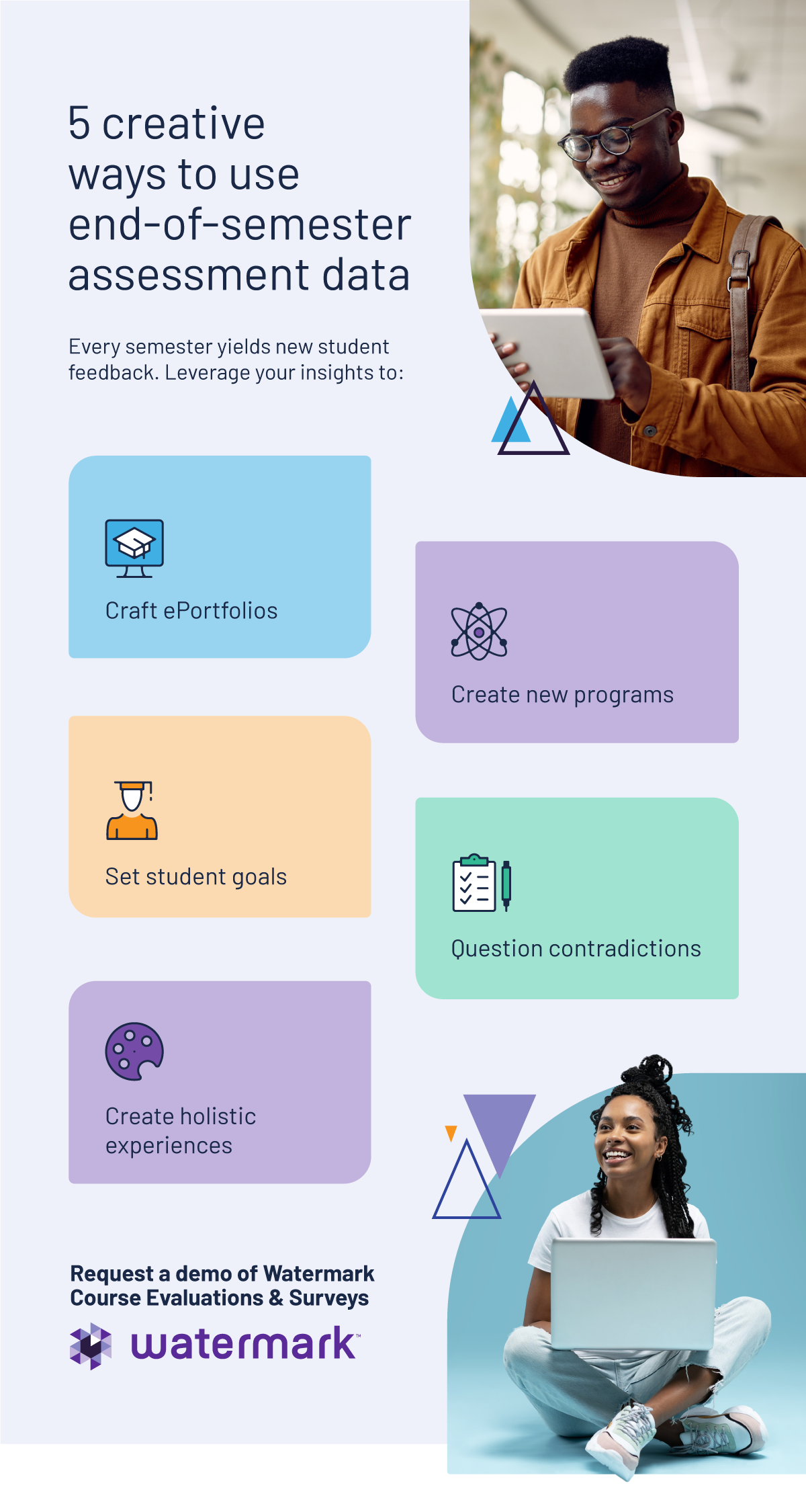

The information from spring evaluations and course surveys can still be used to help faculty make adjustments to their approach to online learning. “If there’s an open-ended question and students are saying, ‘My discussion board was just terrible, it never responded the way I wanted to,’ the faculty may need to adjust the way they’re doing their discussion board,” Smith said. “We are currently giving a lot of professional development to instructors regarding indirect assessment and other ways to assess student learning, but we’re hoping the surveys this semester are going to address some of that and give a lot of good feedback on how to adjust for the future.”

The schools represented in our panel typically see overall response rates of 50-90% for their end-of-semester evaluations, with variation based on how strongly instructors encourage student participation. How do they plan to maintain these results in this time of uncertainty?

All three panelists agreed that seamless integration with their campus learning management system and the use of notifications, reminders, and pop-ups are major contributors to their strong response rates. As students are using the LMS more frequently due to the transition to online learning, the team at Washburn intends to rely even more heavily on pop-up alerts to drive completion. “This semester our students have told us they are getting bombarded with emails and they are just not receptive to another email,” Smith said. “They’ll notice the pop-up before they get into the actual class. If they have three or four classes that need the course evaluation surveys, they’re going to see them as well.”

UCCS takes a similar approach, noting that faculty also use individual strategies to encourage students to complete the questionnaires such as extra credit or setting aside class time. “There’s an integration with Canvas that essentially disrupts the students who are logging into their class and prompts them to complete the course evaluation,” Marschke said.

Swinburne’s data suggests that a large percentage of students prefer to complete their evaluations on mobile devices, so Jones also stressed the importance of using a mobile-friendly platform like Course Evaluations & Surveys (formerly EvaluationKIT) to present the surveys.

Gathering feedback is essential to optimize your institution’s emergency remote teaching experience for both students and faculty. Whether you choose to make changes to your process or stay the course, the message from our panelists is clear: don’t abandon course evaluations during this time of upheaval.

Download the webinar recording to hear more from our panelists, and discover additional ways a survey solution can connect you with students and each other during a crisis.

Submit this form to schedule a meeting with one of our reps to learn more about our solutions. If you need customer support instead, click here.